(from Czech "without cliches" website. Very long story; Pittsburgh years are discussed there are well - I put that i bold letters in the DEEPL translation)

Jiri Hrdina: "F@#$!%ing Lucky Guy"

Either google translated (with pictures):

https://translate.google.com/translate? ... -lucky-guy" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;

Or better translated through DEEPL.COM (every ****="F@#$!%ing"

Spoiler:

**** Lucky Guy

Peripherally, I noticed her starting at me. He was waiting for me and wanted to show me who was boss. That some **** European wasn't gonna prove himself in his league.

I played my first NHL game for Calgary a few days after joining the team, in early March after the 1988 Olympics. Against the Philadelphia Flyers, probably the toughest team in the league. They had Rick Tocchet, one of the most feared players at the time, who could score and pass. He was scoring a lot of points, he just had a streak where he scored almost 20 points in five games. He was on fire, and he was proving it with some devastating hits and some brawling. Just a terror. The kind of dude you don't want to meet at full speed in the middle of the field.

Now he was coming at me to take me down.

I braced myself... We slammed into each other, total collision.

And I was the one who kept going. Tocchet probably thought he'd have an easier time with me, but I was used to fighting. Although it wasn't so common in European hockey at the time, I didn't mind the physical play. If nothing else, in every game with the Russians we tried to cut them as much as possible, which I really enjoyed. I always wanted to hit one.

Tocchet ended up with a dislocated shoulder.

Moments before that, I passed to Jim Peplinski for the winning goal, and he and Joel Otto put me on the line. For that reason alone I would have considered my debut a success, but by not dodging Tochcett and instead flattening him, I immediately made a big mark on the boys. This had even more impact than any assist.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

When I watched the game on TV, even the commentators appreciated how I showed that I wasn't afraid. The journalists also wanted to know how I managed to stand up to such a hard hitter.

I felt that I had attracted attention, and they immediately started to take me on.

Even with that story, I always say that everything was smooth in my career. Smooth. No major setbacks. I experienced a complication maybe in the army, when it was agreed that I would go to Jihlava, but Trenčín, despite expectations, did not take the Lukács brothers together and reached for me. But even there it had its meaning for me from a hockey point of view. Otherwise, I played an important role everywhere since I was young, I was good everywhere. In Sparta and in the national team.

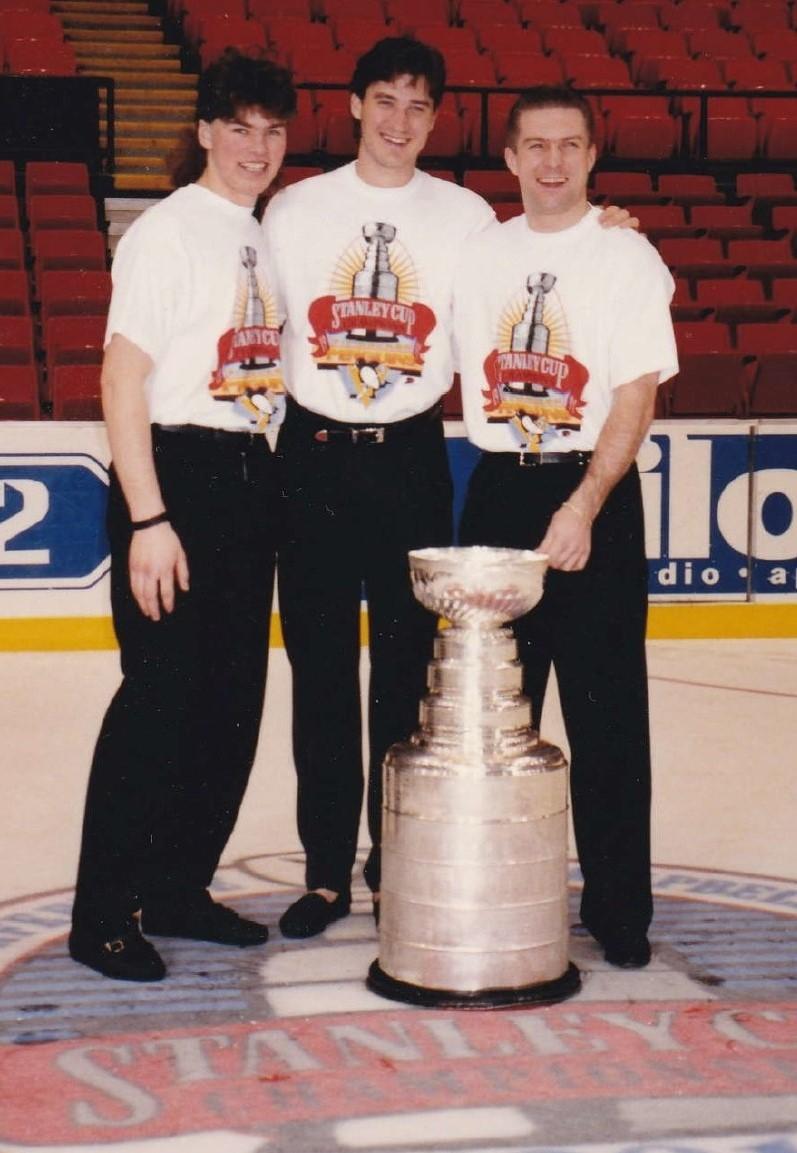

And today, when I tell someone in America that I have three Stanley Cups from five seasons, and only four complete ones, they laugh at me for being a lucky kid.

"**** lucky guy," to be more precise.

A power forward who could finish and combine. That was mine. That's the way I always wanted to play, and that's the way I did. I quickly built up a lot of respect in our league, and because I'm a pretty emotional guy, there was no shortage of situations where things got pretty heated around me. For example, our fights with Jirka Seidl from Pardubice were popular among people, and we went at each other every time we played each other. Because I didn't avoid the places where it hurt, I gradually got smarter even in situations that at first glance seemed to be just about brute force. I knew how to steady myself when someone was coming at me, how to get the puck out of the mêlée in the corner.

In the national team, Vlada Ruzicka, Pavel Richter and I created the ideal line for hockey at that time. Pavel was an amazing technician, Ruzha was a skilled center with a feel for the pass, excellent on the bullpen. He didn't get into fights too much, but that's what I was for. We worked well together, and I impressed NHL scouts with my style of play. At that time, however, we and the Russians were drafted in the last few rounds because they knew we would never play for them anyway. At the beginning of the 1980s, there was still no indication that things were going to change in our country, and the only way to go overseas was to emigrate.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

In June 1984, I learned from the Voice of America, which we listened to, of course, that I had been picked up by the Calgary Flames, but it was immediately clear to me that defection was out of the question. I already had a family and the thought of never seeing them again haunted me. Officially, the comrades only let you go abroad on merit. You had to be 30 years old, and you had to be a world champion. When we managed to win it a year later, I figured that after the Olympics in '88 I'd be good to go. That's what I've got my eye on.

I didn't know much about the NHL. We all devoured The Hockey News, the hockey bible in our day. Anyone who came across it anywhere in the world was taking it home. One issue would circulate in countless hands. But I didn't see my first game until my first national team reunion in Pribram, where Coach Bukač played us a videotape of a Philadelphia Flyers playoff game.

Unbelievable fight.

In the summer of 1987, everything was settled, Cliff Fletcher, the Flames' general manager, came to Prague to see me, and I left for Calgary, where the Olympics were taking place, with a signed contract and with the understanding that I would stay. The tournament didn't go well and I was glad I didn't have to come back, because the failure at home was blamed on me, that I was already in the NHL. That wasn't true, who knew me, knew that I always did everything to win when I stepped on the ice.

While the guys were leaving, I just walked through the corridors of the Saddledome to transfer my gear to another cab and then the driver took me to my hotel. There I lay on the bed and stared at the ceiling, my head full of thoughts about not really knowing what was in store for me.

But what the hell... I'll put on what I can and, worst case scenario, I'll go back to Europe. I've come to terms with that knowledge within myself.

Still, I was nervous as hell at the first training session. No sooner had I opened the locker room door than it dawned on me what I was doing there. I thought of everyone around me as absolute pros and I didn't know if I could ever count myself as one of them.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

I did what felt natural to me. I walked around everyone and shook their hand. Since I've always had a bit of a firmer grip, I learned from the guys in hindsight that they appreciated it. They sensed the right kind of confidence from me.

My introductions even resonated so much that it became a ritual, and I went around the booth before games to encourage everyone.

Joey Nieuwendyk or Lanny McDonald were dudes, the team's workhorses, who took to me immediately. My new line mates Jim Peplinski and Joel Otto or Timmy Hunter did too. So did Hakan Loob, the Swede I started living with, who was a tremendous help from the start, explaining what the NHL was all about. But there were also those who didn't like my arrival. I could sense the animosity from them because they felt I was there to take their spot.

For example, a week after I arrived, they traded the then young Brett Hull to St. Louis.

Anyway, I felt terrible at the first practice. I'd only known Sparta or the national team my whole life and suddenly I was in a completely different environment.

And most importantly, I had a terrible helmet...

The guys were already wearing modern CCMs and the custodians prepared me this crazy square Jofa that we used to play with in Europe. It made me feel like a hobbit amongst the others and after a few days I had it replaced.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyAfter that, it went from strength to strength. My successful debut against Philly, then my first goal in Hartford, followed by another in Quebec. Of the nine games I played before the end of the regular season, I scored in seven. The guys saw that I wasn't a **** and that I could make fun of myself and not get offended when they laughed at me for not understanding the drills.

I also knew at least a little English. The language in the Canadian hockey booth was a bit different than what I had mastered after a year with my teacher in Prague, but I still at least knew what was going on. Thanks to the fact that we were traveling around the world with the national team, I also didn't look with my mouth open at the conveniences of the West. I had an idea of what life was like there, and people from the club, but also Czechoslovak emigrants, of which there were many in Calgary, helped me with whatever I needed. When I came back to camp before the next season, I was ready with everything. I bought a house just outside of the Olympic Village, our girls started going to the local preschool, and I thrived on the ice. I scored twenty-two goals, picked up fifty-four points, played power plays, went on the ice at important times... Pure joy. I also managed to score my first hat trick in Los Angeles right at the beginning of the season. In a game against Gretzky, the greatest player of all time.

I was lucky enough to play in the NHL during his era and that of other greats, so I could see firsthand what they could do.

I remembered Gretzky from the 1977-78 season, when he was 16 and did whatever he wanted with us. Then it stuck with me how he came to the 1982 World Championships in Helsinki and the Canadians stayed in a hotel with us. He scored 92 goals and 212 points for Edmonton that year and we were all blown away by him. We were spying on him every possible moment, what he was doing and how he was acting.

He was just a skinny, pimply kid who squatted at the front desk every night, greasing black jack.

We didn't have the money for that, so at least we went around getting massages.

I managed to score four goals in a game against Hartford in the fall of '88, but the Whalers were the bottom team in the table. A hat trick against the Kings with Gretzky in the lineup was something else. Especially when we beat them that night. An 11-4 record was not unusual in those days, and shootouts like that were common. Especially for us, we didn't lose much that year, we finished as the best team in the regular season and were one of the few teams in modern NHL history to follow that up in the playoffs.

For the first time, I learned how hard the Stanley Cup is.

Yeah, **** lucky guy, I know.

Jiri Hrdina, ice hockey

But for me, first and foremost, it was a huge lesson in professionalism from overseas. Even though I was one of the team's most productive players, I didn't even make the roster for most of the playoffs. The coach used guys he was convinced would help the team more in that moment. I jumped in the first round against Vancouver and then, ironically, in the finals. In the last game in Montreal, when Joey Nieuwendyk took such a hatchet to the arm that he couldn't continue, I was moved to his spot and I finished on the second line.

We went on and on, the mood was great, and after practice, when we all worked the same way, I always looked hopefully at the board on the wall where the coaches wrote the numbers of the players by line. Nobody talked to us, just that's how the lineup for the game was announced.

17... 17... 17... My 17 was nowhere to be found.

So instead of a game, I'd shut myself in the gym for an hour and a half, often with other guys who were in the same boat as me. There were TVs all over the booth with the game on, and we'd lift weights or pedal our bikes to it.

It was mentally challenging to stay on top of things all the time, of course it was. I was expecting it all to be a little bit easier and was surprised by it. My first season in the playoffs, when I was just a punchline, I took it. I understood that the coach, despite my style of play, probably had no idea at first how I would react to the intensity of Stanley Cup games when the refs were still whistling half the little they normally whistled back then. There, when you got wrapped up in front of the net, it was life and death. At least I checked it out first. But even the second season was tougher than I would have thought.

I was far from alone.

Even Lanny McDonald, our captain and an absolute legend, didn't fit into the lineup. He didn't even play half of the final series before returning for the last game to score a crucial goal, his first and only one that playoffs. A story for the movies. Even Jim Peplinski and Timmy Hunter, the assistant captains who were part of building the team for years, are in the winning photo with the Cup in sweatpants because they didn't make it to the four lines that day.

This is where the NHL is ruthless.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

When I arrived at my first camp before this season, I could see that there were over 60 of us. Only twenty-three guys could make the roster. I wasn't worried about my position, I thought that if they didn't want me to play on the first team, they wouldn't have taken me. But still... I was used to the fact that whoever came to the booth played.

My advantage was that as a European I was bringing something different to the team that the Canadian guys back then hadn't experienced that much. Hakan Loob and I were the only Europeans on the club, only later did the Russian Pryachin come along, and in the late eighties we were still more like exotics. Every guy from overseas was the talk of the league.

It was obvious then what a difference there was between our hockey and overseas hockey. In Canada, for example, it was automatically assumed that in a two-on-one situation, the player with the puck would shoot. The goalie would go out on the one with the puck, the defenseman would guard the other without the puck. So if you did a good shoulder roll, signaled and passed, it was a beautiful empty net goal. The Canadians were watching like it was spring.

We were appreciated by our teammates, but to our opponents, we Czechs, Slovaks and Russians were always just "**** commies," **** communists.

But I couldn't even take it personally, I understood that it was part of the game. They yelled at me every game that I was just a piece of **** from Europe, but at the same time they knew I wouldn't be intimidated.

The Tocchet case got out there quickly, but I continued to show that I didn't mind playing hard. I could handle the heated battles of Alberta, as they call the Edmonton duels. I only had one outright fight, in Pittsburgh with a Russian from Toronto. That way I didn't need to prove what a tough guy I was, that's not why I was there. In our time, there weren't even mass fights anymore, when whole bench jumped on the ice, they were forbidden under the threat of heavy penalties. And after all, when something did go wrong and I was on the ice, I got caught up with a Jarri Kurri type, we pulled on each other's jersey to make it look like we were on the ice, but we knew neither of us was interested in any boxing.

Jiri Hrdina, ice hockeyThat doesn't mean you didn't have to be on guard all the time.

You had to.

The likes of Scott Stevens was able to shoot you down even when you weren't playing on his side, his specialty was crossing as a left back across the middle zone and smashing you without you even knowing it. He was capable of disposing of opposing players on the spot. That's how he cancelled out Karyia before Nagano and basically ended Lindros' career. I had the honor of playing him myself at the World Championships in Prague, where he gave me such a beating in the last game that I was in the hospital to receive my gold medal.

Stevens or Marty McSorley, you always had to know exactly where they were on the ice, otherwise they could kill you.

I consider it a success that nobody ever shut me down, but I got beat up a lot of times too. Once you ventured in front of the net, you had to count on axes and crosses, nobody fought you. When I look at the game records from my time today, because I have a few of them tucked away, I can't stop staring at what was happening on that ice. That was pure carnage, I'm not exaggerating. I have to laugh at what they give multi-game penalties for in the NHL these days. The league these days doesn't compare to ours at all. Not at all. I'm not saying it's good or bad, although sometimes I find the effort to keep the game clean really overdone, but it's just not the same.

For us, sometimes you wake up on the bench. And the next substitution, you were already playing again.

"Hunter, you **** *******!"

Timmy Hunter was a cool, smart kid who used to fix old cars in his garage with Jim Peplinski in his spare time. They'd always buy a vintage car and tinker with it. But he played above his time, and that's why he wasn't exactly popular with opposing fans. One time in Philadelphia, we had dinner with him and a couple of other teammates. There was a local NHL expert sitting near us, and he was already a little drunk.

"Hunter, **** you!"

He was cursing, hollering something every once in a while, but Timmy was all over it. He didn't pay any attention to him.

"Hey Hunter, go **** yourself."

After a while, the drunk got up and left. He was back in a minute, seven iron in hand, golf club in hand. He made a beeline for Timmy. But as he was about to cut him, Timmy jumped up.

Pink.

The fighter bought one accurately aimed for the snout and was down in a second. The cops came, took him away, and we finished our meal in peace.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Similar situations happened in our time, we were not puritans. After a few beers, we would go to the club and it was not uncommon when, for example in New York, there was a hundred-metre queue outside the door of a place and we were respectfully let in. There, unlike today's guys, we were able to enjoy ourselves to the fullest because no one was taking pictures of us, we weren't living in the thrall of the world of cell phones and social networks. There were times when someone got so excited that they missed their flight the next morning. Then the boys had to fly themselves at their own expense, there was no one to wait for. There was a seven o'clock departure from the hotel, and anyone who wasn't on the bus at 7:01 was on foot.

But I was past that kind of rampage. I don't make a saint of myself, but I didn't take part in the biggest craziness anymore. You don't do at thirty what you did at twenty, do you... I was a stay-at-home dad, and on trips I lived with Hakan, who was a decent guy. We'd have a beer and then go to the pub, no big deal.

For all the fun some guys could have on their nights off, at the same time, professionally in the NHL, things automatically applied that nobody even had to say. There was an order to everything. From the fact that you always worked overtime at practice to traveling in suits, everyone had to be groomed. In our day, you still flew the line and there was no such thing as someone messing around or drinking in public.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyYou just weren't allowed to fall asleep on the plane, because you could also wake up with shaving foam on your head or a cut tie.

I got to know Theo Fleury in his early days as a laid-back happy guy who didn't cause trouble. I know stories of what he did later on, but I spent almost two seasons with him as a roommate after Hakan left and didn't notice any of that. We only had one extreme experience together.

When our room was robbed in Detroit.

We hung up our suits when we arrived and went out to dinner and a movie. When we got back, we just threw the stuff we were wearing on the chairs, took a shower and went to bed. In the morning, the first thing I said when I opened my closet was, "Theo, what kind of games are you playing with me, where did you put your clothes?"

"What are you doing? I didn't put anything anywhere."

Even the security floor, which required a special key, didn't keep us out. So the hotel boss squeezed the money out of our hands, and instead of breaking up, we went shopping for new outfits so we could go to the game that night. There was no way we were going to go without a jacket and tie.

True, when Theo came back after another summer and was about fifteen pounds heavier and his arms suddenly as big as a bear, I figured there might be a little something a little off, but then again, I never saw him take anything off. And no question, he was a great hockey player. Exceptional. The NHL at the time only wanted a 6-foot-6 player, and he blew into it not even a hundred and seventy. Yet he got under your skin during the game. His specialty was that he'd come at you and jump out of both feet at full speed, he was able to take down dudes a head taller that way. He threw himself into everything without a second thought, and besides his hockey skills, he had a huge heart. He was a fighter who could leave everything on the ice. I remember him fondly.

When I started in the NHL, there were ten Czechoslovaks playing there, give or take. The Stastny brothers, Klíma, Pivoňka, Ježek Svoboda, Fryčer, Musil, Ihnačák and then David Volek. Here and there someone else appeared, but after the revolution more and more young guys started to come. Anyway, we all knew each other in my time, we knew about each other. Either from the national team or simply because there were so few of us that one meeting automatically made us friends.

However, when I saw Franta Musil, who was already playing in Minnesota, at the beginning of my second season, he fooled me into thinking we'd chat right off the bat.

"Hey, Fery!" I yelled at him as we passed each other at the red line.

"**** you, I can't talk to you," he muttered.

Gradually, I realized that the NHL is not much for chit-chat. It was more like before the game, when two fighters would accidentally bump into each other or cut each other while passing through the middle of the field against each other.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

But in the evenings we used to meet the guys from our place. I would always study the lineup of the next opponent beforehand to see if I would see someone I knew, and then we would go out to dinner together and chat. We often talked about what was going on at home. What's coming up.

When are the communists gonna go to hell?

I remember November seventeenth, eighty-nine exactly. We played Buffalo at home the day before and the next game wasn't until the 18th, also in Calgary. That evening, I turned on CNN in the living room, and there were shots of familiar places. The West Coast of Canada is eight hours behind the Czech Republic, so they were already broadcasting what was happening in Prague.

Damn, something is finally happening, I thought.

The next day we called home to find out that events were heating up and it was going to be big. After all, something had been suspected since January, when the cops were dispersing people with water cannons. I had a lot of friends there then and gradually heard stories from them about how they were being loaded into cars and dumped outside Prague. As the cops started beating up students during the demonstrations, it was clear that something had to happen.

Fortunately, my hunch was confirmed, because if it hadn't been for the revolution, I would not have returned from America with my family after my career, I know that for sure. Anyway, November was a big deal, and the Canadians in the locker room were discussing it. They were wondering what was going on in our country.

Also because they had seen Prague themselves shortly before.

We were there for a training camp in September. I'm still proud that it was produced because I came up with the idea. After the Stanley Cup celebrations, when we were trying to figure out how to make training camp more interesting, I suggested that we go to Europe, to Prague. The management agreed, and since the Russians had just let Sergei Makarov join us, Moscow joined in.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

It was a fantastic experience. In Prague, they made me captain and I felt proud to be there when our people got to see the NHL for the first time. Three thousand fans came to our training sessions at the Sports Hall, and we all went without helmets and it was just buzzing because it wasn't usual here. We slept at the Intercontinental, where I got the guys to exchange money so they wouldn't get ripped off by the bouncers. All they needed was two hundred dollars and they lived like kings for a week, because a Pilsner beer cost three crowns. They were constantly miscalculating and didn't understand that a pint cost a few cents, while in Canada they paid two dollars for it. A lot of my teammates still remember this and remind me of it when we meet. Just like the White Horse in Staromák, the bar where we had a nice evening... After all, I still had a lot of friends in Prague, so we had open doors everywhere.

Unfortunately, the games looked like that. Our national team that we faced had been preparing for us for three months after various training camps, they unleashed a young line of Jagr, Reichel, Holík on us and we lost both times.

But the guys were still excited. First of all because of the crystal my friend helped them buy, which had to be sent in a special box via the embassy, but mostly because it wasn't so much fun in Moscow. There was still a heavy totalitarian regime there.

In mid-December 1990, my parents were on their way to Calgary and we were on a trip with the team. I didn't do well at all, I was out of the lineup for a couple of games. After a morning warm-up and a team lunch in Los Angeles, I went to bed in my room before the phone woke me up half an hour later. General manager Cliff Fletcher called to say that they were in the room with coach Doug Riegsbrough and to come see them.

"We have news for you, we've made a decision. We've traded you to the Pittsburgh Penguins," they told me without much talking around.

I was absolutely not expecting something like that.

My first reaction was that I wasn't going anywhere. Sorry, but I'm going back to Europe. With that, I packed up my stuff in my room and said goodbye to Theo. The assistant GM drove me to the airport, and upon returning to Calgary, I was scheduled to leave for Pittsburgh the next day. My wife and I had endless debates that night about whether or not to fly in the morning. I couldn't imagine that after we were finally settled in properly and the girls started school, I was suddenly going to take my family and move them across the continent. Plus, Pittsburgh was stuck at the bottom of their division at the time, and Mario Lemieux, while a top-notch superstar, hadn't played in almost a year due to a back injury, and no one knew if he'd even be back.

No, I really didn't want to.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Let's go to my parents... We passed each other at the airport without meeting. Out of the month they were visiting us in Calgary, we saw each other two days on Christmas.

Eventually, I pulled myself together and went to Pittsburgh. I had no idea what to expect, but I vowed to show Calgary that I wasn't such a bad player that they would get rid of me. That's how I took the trade. That I wasn't good enough anymore, that's why they got rid of me.

Nobody told me that the Penguins have this long-haired kid from Kladno, a tremendous talent, who secretly cries in the shower because he doesn't get along with anybody in the locker room and he misses them. I figured out after a while that Craig Patrick, the Pittsburgh GM, found out how I was helping Robert Reichl in Calgary in his early days in the NHL. Then when the Flames weren't playing me, he sensed a chance to bring me in to bang with young Jagr.

Not once did I hear that from anyone in the clubhouse. It was only years later that I heard from people who took credit for it and told me that they convinced Craig to get me as Jagr's tutor.

For myself, it was important that I scored a goal in the first game against Calgary and felt a great sense of satisfaction. And the fact that Mario came back soon after and we started to make an unbelievable run.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey And it went well with Jagr. They sat us next to each other in the booth, he took me to the Nemec family where he lived, and we became friends. I wasn't playing teacher, because Jarda really just needed someone he felt comfortable around and could talk to. Someone who could help him get comfortable in a new world and who could explain to him in a clear way what the NHL is all about and how to approach certain situations. It was small things, but in sum, pretty important. The same little things that Hakan explained to me in my early days in Calgary and that I just passed on, first to Alby Reichl and now to Jagr.

There was only one problem with him. Sometimes he would step on the gas in the car and he didn't want to pay the fines. He even ended up in court a few times and Craig had to vouch for him with the police. That's when he talked a lot of sense into Jard.

I had no idea at the time what a phenomenal hockey player he would grow up to be. Yes, I'd seen him as a youngster in the national team, but that didn't mean that much. But it's true that he showed incredible things in his first seasons in the NHL. After all, everyone remembers his famous goal in the '92 finals against Chicago, when he flipped Franta Kucherov between his legs and sent a backhand pass to Belfour.

I also had my moment of glory next to him when I managed to score two goals in the first playoff game in the seventh game of the opening round against the Devils. Just recently I saw a table on Canadian TV showing who had two goals for Pittsburgh in the seventh game, because nobody had more. There was Crosby, Rust, Talbot. And the Hero.

Honestly: The goal I'll always remember as the one that made my dream come true will be the lid call on Tretiak after Ruz's pass down the blue line. He got us silver at the 1983 World Championships. But this game against New Jersey is one to remember. I had a great feeling inside at the time, thinking, I guess I'm not that old yet. On that first and finally winning goal, the Russians were on the ice, i.e. defenseman Fetisov Kasatonov. It always made me happy when I helped beat them.

Ironically, it was also my only two goals in the playoffs ever.

Two goals, three Stanley Cups. **** lucky guy, you know.

I was lucky as hell to get on two fantastic teams in the NHL. In Calgary, incredible teamwork led us to the Cup, we were able to dominate through hard work even without pure superstars, we stuck together as one big group of friends. It was in Pittsburgh that an incredibly loaded roster full of amazing players finally clicked. Paul Coffey, Larry Murphy, Ron Francis, Kevin Stevens, Marc Recchi, Jagr, they were all great guys. And finally, we got that Rick Tocchet guy.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyAnd Mario was the king of all.

The way he came back from the sideline speaks volumes about how unique a player he was.

After ten months without hockey, he got on his bike for three days, then took to the ice with us twice, and after less than a week of light training, he went to play in Quebec, where he recorded three goals. After three games he was 2+4 and continued in that vein.

He was a classic leader by example. One who leads by example. He wasn't one for making speeches, if he said anything it was more likely to be in the playoffs, but his excellence at the plate was unmatched. He gave you confidence just by seeing him in the locker room getting dressed in the gear next to you. Other than that, he was a friendly, nice guy. He talked to everyone as equals, no condescension. When we finally made it to the Stanley Cup with his great help, he invited the whole team over to his house.

We ended up with the Cup in the pool there, which is one of my fondest memories of the celebration.

Then, my second year in Pittsburgh, I got to know another one-of-a-kind person in the league. Scotty Bowman took over and I found out why he is the most successful coach in history.

In games, it should be added.

There, he showed a really hard-to-describe feel for knowing what line was doing well and on whom. He deployed players like no one else and was able to keep the team on a roll. He was incredibly knowledgeable about hockey, knew everyone's strengths and weaknesses and was able to take advantage of them.

It was just his training sessions that were crazy.

As detailed as he was, he would cling to complete useless things, like we could only turn to one side during a particular drill or something. We all resented it, and morale went down. For example, when he would chase us around in circles and we had to speed up on a whistle, or slow down on the next one, I would whistle to him that there was a maglajs in it. Then he'd yell angrily who was doing it.

So Mario went to Craig and told him that it couldn't be done that way, that the assistants should run the training sessions and that Scotty should only ever show up for the game.

They were both able to accept that, and that helped us to our second Stanley Cup.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

The celebrations, which were unforgettable in Calgary when tens of thousands of people lined the streets during the parade, were worth it here both times. The first year we drove through the city to the 60,000-seat Three Rivers Stadium for American football and baseball. We were each driven around in a convertible, making a circle before being dropped off at the podium. The year after that was celebrated in the local central park, which was again packed with people. I remember images from here that will never fade from my mind. Partly because I recorded them on camera.

Yeah, even back then. It wasn't quite a GoPro, and the picture wasn't exactly HD quality, but a small one-handed camera was something you could get. Admittedly, just about anyone doesn't have such a treasure at home, my friends and I would occasionally play the footage.

But then once we went on to the boat party, I didn't record anything. I couldn't.

Shortly after the second Pittsburgh party, I made an appointment at Craig's office. He welcomed me, saying I'd get so-and-so raises, but that he could only give me a two-year contract.

I said, "Craig, Craig, wait. I'm not here to sign a contract. I'm here to say goodbye to you. I'm done with hockey."

It was quiet for a while.

"Are you serious?"

"Yeah. Dead serious."

He was expecting me to bid on money and contract length, and I surprised him with this announcement. We shook hands and it was done. To this day, Craig gives credit to the fact that there have been so many times in his career that he's offered someone an extension and better money and they turned him down. But I felt enough was enough. I was fed up with hockey after seventeen years of playing professionally. My shoulder was hurting, I was finishing the season with a knee brace due to strained ligaments, and I couldn't imagine starting summer training again after another Stanley Cup celebration. I could have continued in Switzerland or Germany, I had offers from there as well, but the idea that after what I had experienced I would be back on buses somewhere again, discouraged me as well.

World champion, three times Stanley Cup... I figured that this is enough, I can hang it up with peace of mind and rather than risk killing my body, I'd rather keep my strength up and play sports just for fun. My family and I went straight to Hawaii and that was the end of my hockey career.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Like this, not definitively. There was one more little twitch.

I was persuaded by old Spartans, Standa Hajdušek, Karel Holý, Láďa Vlček and others, that it was a great idea to play with them in the second league for Velké Popovice.

And so I did. I'll go for it, so I can sweat and enjoy a beer for lunch, right...

But we had a team full of amateurs, guys who came to play after work. They'd just been promoted from the county competition, and they weren't really up to the higher competition. My fourth game we came to Havlíčkův Brod.

It was sold out, and they borrowed a line of young guys from Pardubice. We got 1:14.

I scored our only goal. Basically, almost like Lanny McDonald in his last game, you could say... But seriously, I immediately told the guys that I'm sorry, but after everything I've been through, I'm really not up to this anymore. I've never played a competition since. Occasionally, I'll just go out with the old guard, but over the years I've gotten to enjoy just being able to knock somebody around, no golfers or points. And I keep myself busy with tennis and golf, that's enough for me.

Mostly, I'm always at hockey, so I don't miss anything in life.

No sooner was I done in Pittsburgh than I took advantage of a previous arrangement with Calgary and started working as their scout. In the early 1990s, when the NHL was opening up more and more to Europeans, clubs were gradually looking for someone to scout players for them here. I was tempted by this opportunity, I couldn't stand to do nothing, so I went for it.

I remember my first assignment exactly, a tournament of 20 boys of the year 1974 in Klatovy. They sent a scout for North America to help me learn the ropes and show me how to do things. Player reports had to have a certain structure even then.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

And they were written by hand, no computer. I didn't get one until a few years later, but it was just a pre-flood one with a black screen and a blinking white cursor. After seventeen seasons, when after a game I would maybe lie down in my room, turn on the TV and have a beer, I would suddenly be writing several-page essays and then spend eternity on the fax machine. I'd cram in maybe twenty-five A4s, then find out that it came out wrong on the other side of the world, so I'd do it all over again... I was learning completely new things. And I've done a lot of traveling that I've planned for myself. Before the internet, it was something crazy. I was sneakily getting stats for caps and Calgary logo t-shirts, begging youth national team nominations from coaches, and relying on one assistant in Russia to get me into all the stadiums.

The lumberjack days of scouting.

But it was all the more fun. Gradually we formed a group of guys, former opposing players and teammates, who we would meet at various times around the world and sometimes travel with. We have a rule that we don't talk about the players together, but on the other hand, nowadays you don't have a chance to hide someone from the competition anyway. The hockey world is scouted to the last bit, it's just about what type of players your club needs. Back in the 90's you could find someone in a competition that others had no idea about, but those days are long gone.

It's also nice to see how priorities have changed over time. When I started, 5'8" was a small player. The priority was heartthrobs, strong guys who maybe didn't even have to know how to skate that much, but most importantly, not to be afraid.

Today it's the opposite. It probably wouldn't happen again that we all agreed in Calgary before the 1997 draft that we wanted the Russian Samsonov, but our head scout, an old school guy, turned him down. He's small.

We took Daniel Tkazczuk, whose NHL career ended at 19 games, with the sixth pick, and Samsonov was snatched up by Boston two spots behind us. As a 19-year-old, he scored twenty-two goals the very next season and ended up collecting nearly 600 points in the league.

Honestly, you don't have to be a big expert to be impressed by the smartest guys. Just watch the game and they will come out of the game themselves, they will come to you. There are clouds of those who ride up and down, but talent and feel for the game is something else entirely. That's how I used to be blown away by David Výborný, and later by Kuba Voracek, I always liked his style and commitment.

But I've seen a lot of teenagers next to him, soaping each other up... I play around 200 games a year. For Dallas, where I moved in 1999, I'm now in charge of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Germany and Switzerland. At the beginning of the season, I always go around to all the junior teams and clubs where the youngsters play to map out the year, and then I gradually go to see the guys who interest me and send reports about them to America. On top of that, of course, I see all the national events of the 18s and 20s.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Most often, sometimes on the way back from Switzerland in a blizzard, I wonder if it's all still worth it, because the work has no tangible result. It depends on so many factors... It all comes down to how your club finishes in a given season, which has a major impact on the order of draft picks. Admittedly, as scouts, we then prepare a prioritized list of players for the general manager, but that list is basically just crossed off on draft day as teams ahead of you take the names you pick. And even if you're just reaching for someone you really wanted, you're simply taking an unfinished product. An 18-year-old kid who meets some chick a year later and loses the will to work for it...

But that's why we interview players, we take a personal interest in them, we find out what kind of families they come from, and after the season we interview the selected ones. I've had a lot of years of questions, and I try to find out as much as I can. But the agents prepare the players to answer them the way the clubs want to hear them. Sometimes I feel like I'm having a chat with a robot.

But at the same time, the same thing still applies as in my day.

When anyone steps on the ice in the NHL, they have to show they can do something. That they can do it. And when a fearsome opponent comes at him, he shouldn't duck.

Yeah, a lot of these guys are gonna get to the NHL a lot easier than we had to. But that doesn't mean they're gonna be **** lucky guys.

Peripherally, I noticed her starting at me. He was waiting for me and wanted to show me who was boss. That some **** European wasn't gonna prove himself in his league.

I played my first NHL game for Calgary a few days after joining the team, in early March after the 1988 Olympics. Against the Philadelphia Flyers, probably the toughest team in the league. They had Rick Tocchet, one of the most feared players at the time, who could score and pass. He was scoring a lot of points, he just had a streak where he scored almost 20 points in five games. He was on fire, and he was proving it with some devastating hits and some brawling. Just a terror. The kind of dude you don't want to meet at full speed in the middle of the field.

Now he was coming at me to take me down.

I braced myself... We slammed into each other, total collision.

And I was the one who kept going. Tocchet probably thought he'd have an easier time with me, but I was used to fighting. Although it wasn't so common in European hockey at the time, I didn't mind the physical play. If nothing else, in every game with the Russians we tried to cut them as much as possible, which I really enjoyed. I always wanted to hit one.

Tocchet ended up with a dislocated shoulder.

Moments before that, I passed to Jim Peplinski for the winning goal, and he and Joel Otto put me on the line. For that reason alone I would have considered my debut a success, but by not dodging Tochcett and instead flattening him, I immediately made a big mark on the boys. This had even more impact than any assist.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

When I watched the game on TV, even the commentators appreciated how I showed that I wasn't afraid. The journalists also wanted to know how I managed to stand up to such a hard hitter.

I felt that I had attracted attention, and they immediately started to take me on.

Even with that story, I always say that everything was smooth in my career. Smooth. No major setbacks. I experienced a complication maybe in the army, when it was agreed that I would go to Jihlava, but Trenčín, despite expectations, did not take the Lukács brothers together and reached for me. But even there it had its meaning for me from a hockey point of view. Otherwise, I played an important role everywhere since I was young, I was good everywhere. In Sparta and in the national team.

And today, when I tell someone in America that I have three Stanley Cups from five seasons, and only four complete ones, they laugh at me for being a lucky kid.

"**** lucky guy," to be more precise.

A power forward who could finish and combine. That was mine. That's the way I always wanted to play, and that's the way I did. I quickly built up a lot of respect in our league, and because I'm a pretty emotional guy, there was no shortage of situations where things got pretty heated around me. For example, our fights with Jirka Seidl from Pardubice were popular among people, and we went at each other every time we played each other. Because I didn't avoid the places where it hurt, I gradually got smarter even in situations that at first glance seemed to be just about brute force. I knew how to steady myself when someone was coming at me, how to get the puck out of the mêlée in the corner.

In the national team, Vlada Ruzicka, Pavel Richter and I created the ideal line for hockey at that time. Pavel was an amazing technician, Ruzha was a skilled center with a feel for the pass, excellent on the bullpen. He didn't get into fights too much, but that's what I was for. We worked well together, and I impressed NHL scouts with my style of play. At that time, however, we and the Russians were drafted in the last few rounds because they knew we would never play for them anyway. At the beginning of the 1980s, there was still no indication that things were going to change in our country, and the only way to go overseas was to emigrate.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

In June 1984, I learned from the Voice of America, which we listened to, of course, that I had been picked up by the Calgary Flames, but it was immediately clear to me that defection was out of the question. I already had a family and the thought of never seeing them again haunted me. Officially, the comrades only let you go abroad on merit. You had to be 30 years old, and you had to be a world champion. When we managed to win it a year later, I figured that after the Olympics in '88 I'd be good to go. That's what I've got my eye on.

I didn't know much about the NHL. We all devoured The Hockey News, the hockey bible in our day. Anyone who came across it anywhere in the world was taking it home. One issue would circulate in countless hands. But I didn't see my first game until my first national team reunion in Pribram, where Coach Bukač played us a videotape of a Philadelphia Flyers playoff game.

Unbelievable fight.

In the summer of 1987, everything was settled, Cliff Fletcher, the Flames' general manager, came to Prague to see me, and I left for Calgary, where the Olympics were taking place, with a signed contract and with the understanding that I would stay. The tournament didn't go well and I was glad I didn't have to come back, because the failure at home was blamed on me, that I was already in the NHL. That wasn't true, who knew me, knew that I always did everything to win when I stepped on the ice.

While the guys were leaving, I just walked through the corridors of the Saddledome to transfer my gear to another cab and then the driver took me to my hotel. There I lay on the bed and stared at the ceiling, my head full of thoughts about not really knowing what was in store for me.

But what the hell... I'll put on what I can and, worst case scenario, I'll go back to Europe. I've come to terms with that knowledge within myself.

Still, I was nervous as hell at the first training session. No sooner had I opened the locker room door than it dawned on me what I was doing there. I thought of everyone around me as absolute pros and I didn't know if I could ever count myself as one of them.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

I did what felt natural to me. I walked around everyone and shook their hand. Since I've always had a bit of a firmer grip, I learned from the guys in hindsight that they appreciated it. They sensed the right kind of confidence from me.

My introductions even resonated so much that it became a ritual, and I went around the booth before games to encourage everyone.

Joey Nieuwendyk or Lanny McDonald were dudes, the team's workhorses, who took to me immediately. My new line mates Jim Peplinski and Joel Otto or Timmy Hunter did too. So did Hakan Loob, the Swede I started living with, who was a tremendous help from the start, explaining what the NHL was all about. But there were also those who didn't like my arrival. I could sense the animosity from them because they felt I was there to take their spot.

For example, a week after I arrived, they traded the then young Brett Hull to St. Louis.

Anyway, I felt terrible at the first practice. I'd only known Sparta or the national team my whole life and suddenly I was in a completely different environment.

And most importantly, I had a terrible helmet...

The guys were already wearing modern CCMs and the custodians prepared me this crazy square Jofa that we used to play with in Europe. It made me feel like a hobbit amongst the others and after a few days I had it replaced.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyAfter that, it went from strength to strength. My successful debut against Philly, then my first goal in Hartford, followed by another in Quebec. Of the nine games I played before the end of the regular season, I scored in seven. The guys saw that I wasn't a **** and that I could make fun of myself and not get offended when they laughed at me for not understanding the drills.

I also knew at least a little English. The language in the Canadian hockey booth was a bit different than what I had mastered after a year with my teacher in Prague, but I still at least knew what was going on. Thanks to the fact that we were traveling around the world with the national team, I also didn't look with my mouth open at the conveniences of the West. I had an idea of what life was like there, and people from the club, but also Czechoslovak emigrants, of which there were many in Calgary, helped me with whatever I needed. When I came back to camp before the next season, I was ready with everything. I bought a house just outside of the Olympic Village, our girls started going to the local preschool, and I thrived on the ice. I scored twenty-two goals, picked up fifty-four points, played power plays, went on the ice at important times... Pure joy. I also managed to score my first hat trick in Los Angeles right at the beginning of the season. In a game against Gretzky, the greatest player of all time.

I was lucky enough to play in the NHL during his era and that of other greats, so I could see firsthand what they could do.

I remembered Gretzky from the 1977-78 season, when he was 16 and did whatever he wanted with us. Then it stuck with me how he came to the 1982 World Championships in Helsinki and the Canadians stayed in a hotel with us. He scored 92 goals and 212 points for Edmonton that year and we were all blown away by him. We were spying on him every possible moment, what he was doing and how he was acting.

He was just a skinny, pimply kid who squatted at the front desk every night, greasing black jack.

We didn't have the money for that, so at least we went around getting massages.

I managed to score four goals in a game against Hartford in the fall of '88, but the Whalers were the bottom team in the table. A hat trick against the Kings with Gretzky in the lineup was something else. Especially when we beat them that night. An 11-4 record was not unusual in those days, and shootouts like that were common. Especially for us, we didn't lose much that year, we finished as the best team in the regular season and were one of the few teams in modern NHL history to follow that up in the playoffs.

For the first time, I learned how hard the Stanley Cup is.

Yeah, **** lucky guy, I know.

Jiri Hrdina, ice hockey

But for me, first and foremost, it was a huge lesson in professionalism from overseas. Even though I was one of the team's most productive players, I didn't even make the roster for most of the playoffs. The coach used guys he was convinced would help the team more in that moment. I jumped in the first round against Vancouver and then, ironically, in the finals. In the last game in Montreal, when Joey Nieuwendyk took such a hatchet to the arm that he couldn't continue, I was moved to his spot and I finished on the second line.

We went on and on, the mood was great, and after practice, when we all worked the same way, I always looked hopefully at the board on the wall where the coaches wrote the numbers of the players by line. Nobody talked to us, just that's how the lineup for the game was announced.

17... 17... 17... My 17 was nowhere to be found.

So instead of a game, I'd shut myself in the gym for an hour and a half, often with other guys who were in the same boat as me. There were TVs all over the booth with the game on, and we'd lift weights or pedal our bikes to it.

It was mentally challenging to stay on top of things all the time, of course it was. I was expecting it all to be a little bit easier and was surprised by it. My first season in the playoffs, when I was just a punchline, I took it. I understood that the coach, despite my style of play, probably had no idea at first how I would react to the intensity of Stanley Cup games when the refs were still whistling half the little they normally whistled back then. There, when you got wrapped up in front of the net, it was life and death. At least I checked it out first. But even the second season was tougher than I would have thought.

I was far from alone.

Even Lanny McDonald, our captain and an absolute legend, didn't fit into the lineup. He didn't even play half of the final series before returning for the last game to score a crucial goal, his first and only one that playoffs. A story for the movies. Even Jim Peplinski and Timmy Hunter, the assistant captains who were part of building the team for years, are in the winning photo with the Cup in sweatpants because they didn't make it to the four lines that day.

This is where the NHL is ruthless.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

When I arrived at my first camp before this season, I could see that there were over 60 of us. Only twenty-three guys could make the roster. I wasn't worried about my position, I thought that if they didn't want me to play on the first team, they wouldn't have taken me. But still... I was used to the fact that whoever came to the booth played.

My advantage was that as a European I was bringing something different to the team that the Canadian guys back then hadn't experienced that much. Hakan Loob and I were the only Europeans on the club, only later did the Russian Pryachin come along, and in the late eighties we were still more like exotics. Every guy from overseas was the talk of the league.

It was obvious then what a difference there was between our hockey and overseas hockey. In Canada, for example, it was automatically assumed that in a two-on-one situation, the player with the puck would shoot. The goalie would go out on the one with the puck, the defenseman would guard the other without the puck. So if you did a good shoulder roll, signaled and passed, it was a beautiful empty net goal. The Canadians were watching like it was spring.

We were appreciated by our teammates, but to our opponents, we Czechs, Slovaks and Russians were always just "**** commies," **** communists.

But I couldn't even take it personally, I understood that it was part of the game. They yelled at me every game that I was just a piece of **** from Europe, but at the same time they knew I wouldn't be intimidated.

The Tocchet case got out there quickly, but I continued to show that I didn't mind playing hard. I could handle the heated battles of Alberta, as they call the Edmonton duels. I only had one outright fight, in Pittsburgh with a Russian from Toronto. That way I didn't need to prove what a tough guy I was, that's not why I was there. In our time, there weren't even mass fights anymore, when whole bench jumped on the ice, they were forbidden under the threat of heavy penalties. And after all, when something did go wrong and I was on the ice, I got caught up with a Jarri Kurri type, we pulled on each other's jersey to make it look like we were on the ice, but we knew neither of us was interested in any boxing.

Jiri Hrdina, ice hockeyThat doesn't mean you didn't have to be on guard all the time.

You had to.

The likes of Scott Stevens was able to shoot you down even when you weren't playing on his side, his specialty was crossing as a left back across the middle zone and smashing you without you even knowing it. He was capable of disposing of opposing players on the spot. That's how he cancelled out Karyia before Nagano and basically ended Lindros' career. I had the honor of playing him myself at the World Championships in Prague, where he gave me such a beating in the last game that I was in the hospital to receive my gold medal.

Stevens or Marty McSorley, you always had to know exactly where they were on the ice, otherwise they could kill you.

I consider it a success that nobody ever shut me down, but I got beat up a lot of times too. Once you ventured in front of the net, you had to count on axes and crosses, nobody fought you. When I look at the game records from my time today, because I have a few of them tucked away, I can't stop staring at what was happening on that ice. That was pure carnage, I'm not exaggerating. I have to laugh at what they give multi-game penalties for in the NHL these days. The league these days doesn't compare to ours at all. Not at all. I'm not saying it's good or bad, although sometimes I find the effort to keep the game clean really overdone, but it's just not the same.

For us, sometimes you wake up on the bench. And the next substitution, you were already playing again.

"Hunter, you **** *******!"

Timmy Hunter was a cool, smart kid who used to fix old cars in his garage with Jim Peplinski in his spare time. They'd always buy a vintage car and tinker with it. But he played above his time, and that's why he wasn't exactly popular with opposing fans. One time in Philadelphia, we had dinner with him and a couple of other teammates. There was a local NHL expert sitting near us, and he was already a little drunk.

"Hunter, **** you!"

He was cursing, hollering something every once in a while, but Timmy was all over it. He didn't pay any attention to him.

"Hey Hunter, go **** yourself."

After a while, the drunk got up and left. He was back in a minute, seven iron in hand, golf club in hand. He made a beeline for Timmy. But as he was about to cut him, Timmy jumped up.

Pink.

The fighter bought one accurately aimed for the snout and was down in a second. The cops came, took him away, and we finished our meal in peace.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Similar situations happened in our time, we were not puritans. After a few beers, we would go to the club and it was not uncommon when, for example in New York, there was a hundred-metre queue outside the door of a place and we were respectfully let in. There, unlike today's guys, we were able to enjoy ourselves to the fullest because no one was taking pictures of us, we weren't living in the thrall of the world of cell phones and social networks. There were times when someone got so excited that they missed their flight the next morning. Then the boys had to fly themselves at their own expense, there was no one to wait for. There was a seven o'clock departure from the hotel, and anyone who wasn't on the bus at 7:01 was on foot.

But I was past that kind of rampage. I don't make a saint of myself, but I didn't take part in the biggest craziness anymore. You don't do at thirty what you did at twenty, do you... I was a stay-at-home dad, and on trips I lived with Hakan, who was a decent guy. We'd have a beer and then go to the pub, no big deal.

For all the fun some guys could have on their nights off, at the same time, professionally in the NHL, things automatically applied that nobody even had to say. There was an order to everything. From the fact that you always worked overtime at practice to traveling in suits, everyone had to be groomed. In our day, you still flew the line and there was no such thing as someone messing around or drinking in public.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyYou just weren't allowed to fall asleep on the plane, because you could also wake up with shaving foam on your head or a cut tie.

I got to know Theo Fleury in his early days as a laid-back happy guy who didn't cause trouble. I know stories of what he did later on, but I spent almost two seasons with him as a roommate after Hakan left and didn't notice any of that. We only had one extreme experience together.

When our room was robbed in Detroit.

We hung up our suits when we arrived and went out to dinner and a movie. When we got back, we just threw the stuff we were wearing on the chairs, took a shower and went to bed. In the morning, the first thing I said when I opened my closet was, "Theo, what kind of games are you playing with me, where did you put your clothes?"

"What are you doing? I didn't put anything anywhere."

Even the security floor, which required a special key, didn't keep us out. So the hotel boss squeezed the money out of our hands, and instead of breaking up, we went shopping for new outfits so we could go to the game that night. There was no way we were going to go without a jacket and tie.

True, when Theo came back after another summer and was about fifteen pounds heavier and his arms suddenly as big as a bear, I figured there might be a little something a little off, but then again, I never saw him take anything off. And no question, he was a great hockey player. Exceptional. The NHL at the time only wanted a 6-foot-6 player, and he blew into it not even a hundred and seventy. Yet he got under your skin during the game. His specialty was that he'd come at you and jump out of both feet at full speed, he was able to take down dudes a head taller that way. He threw himself into everything without a second thought, and besides his hockey skills, he had a huge heart. He was a fighter who could leave everything on the ice. I remember him fondly.

When I started in the NHL, there were ten Czechoslovaks playing there, give or take. The Stastny brothers, Klíma, Pivoňka, Ježek Svoboda, Fryčer, Musil, Ihnačák and then David Volek. Here and there someone else appeared, but after the revolution more and more young guys started to come. Anyway, we all knew each other in my time, we knew about each other. Either from the national team or simply because there were so few of us that one meeting automatically made us friends.

However, when I saw Franta Musil, who was already playing in Minnesota, at the beginning of my second season, he fooled me into thinking we'd chat right off the bat.

"Hey, Fery!" I yelled at him as we passed each other at the red line.

"**** you, I can't talk to you," he muttered.

Gradually, I realized that the NHL is not much for chit-chat. It was more like before the game, when two fighters would accidentally bump into each other or cut each other while passing through the middle of the field against each other.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

But in the evenings we used to meet the guys from our place. I would always study the lineup of the next opponent beforehand to see if I would see someone I knew, and then we would go out to dinner together and chat. We often talked about what was going on at home. What's coming up.

When are the communists gonna go to hell?

I remember November seventeenth, eighty-nine exactly. We played Buffalo at home the day before and the next game wasn't until the 18th, also in Calgary. That evening, I turned on CNN in the living room, and there were shots of familiar places. The West Coast of Canada is eight hours behind the Czech Republic, so they were already broadcasting what was happening in Prague.

Damn, something is finally happening, I thought.

The next day we called home to find out that events were heating up and it was going to be big. After all, something had been suspected since January, when the cops were dispersing people with water cannons. I had a lot of friends there then and gradually heard stories from them about how they were being loaded into cars and dumped outside Prague. As the cops started beating up students during the demonstrations, it was clear that something had to happen.

Fortunately, my hunch was confirmed, because if it hadn't been for the revolution, I would not have returned from America with my family after my career, I know that for sure. Anyway, November was a big deal, and the Canadians in the locker room were discussing it. They were wondering what was going on in our country.

Also because they had seen Prague themselves shortly before.

We were there for a training camp in September. I'm still proud that it was produced because I came up with the idea. After the Stanley Cup celebrations, when we were trying to figure out how to make training camp more interesting, I suggested that we go to Europe, to Prague. The management agreed, and since the Russians had just let Sergei Makarov join us, Moscow joined in.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

It was a fantastic experience. In Prague, they made me captain and I felt proud to be there when our people got to see the NHL for the first time. Three thousand fans came to our training sessions at the Sports Hall, and we all went without helmets and it was just buzzing because it wasn't usual here. We slept at the Intercontinental, where I got the guys to exchange money so they wouldn't get ripped off by the bouncers. All they needed was two hundred dollars and they lived like kings for a week, because a Pilsner beer cost three crowns. They were constantly miscalculating and didn't understand that a pint cost a few cents, while in Canada they paid two dollars for it. A lot of my teammates still remember this and remind me of it when we meet. Just like the White Horse in Staromák, the bar where we had a nice evening... After all, I still had a lot of friends in Prague, so we had open doors everywhere.

Unfortunately, the games looked like that. Our national team that we faced had been preparing for us for three months after various training camps, they unleashed a young line of Jagr, Reichel, Holík on us and we lost both times.

But the guys were still excited. First of all because of the crystal my friend helped them buy, which had to be sent in a special box via the embassy, but mostly because it wasn't so much fun in Moscow. There was still a heavy totalitarian regime there.

In mid-December 1990, my parents were on their way to Calgary and we were on a trip with the team. I didn't do well at all, I was out of the lineup for a couple of games. After a morning warm-up and a team lunch in Los Angeles, I went to bed in my room before the phone woke me up half an hour later. General manager Cliff Fletcher called to say that they were in the room with coach Doug Riegsbrough and to come see them.

"We have news for you, we've made a decision. We've traded you to the Pittsburgh Penguins," they told me without much talking around.

I was absolutely not expecting something like that.

My first reaction was that I wasn't going anywhere. Sorry, but I'm going back to Europe. With that, I packed up my stuff in my room and said goodbye to Theo. The assistant GM drove me to the airport, and upon returning to Calgary, I was scheduled to leave for Pittsburgh the next day. My wife and I had endless debates that night about whether or not to fly in the morning. I couldn't imagine that after we were finally settled in properly and the girls started school, I was suddenly going to take my family and move them across the continent. Plus, Pittsburgh was stuck at the bottom of their division at the time, and Mario Lemieux, while a top-notch superstar, hadn't played in almost a year due to a back injury, and no one knew if he'd even be back.

No, I really didn't want to.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Let's go to my parents... We passed each other at the airport without meeting. Out of the month they were visiting us in Calgary, we saw each other two days on Christmas.

Eventually, I pulled myself together and went to Pittsburgh. I had no idea what to expect, but I vowed to show Calgary that I wasn't such a bad player that they would get rid of me. That's how I took the trade. That I wasn't good enough anymore, that's why they got rid of me.

Nobody told me that the Penguins have this long-haired kid from Kladno, a tremendous talent, who secretly cries in the shower because he doesn't get along with anybody in the locker room and he misses them. I figured out after a while that Craig Patrick, the Pittsburgh GM, found out how I was helping Robert Reichl in Calgary in his early days in the NHL. Then when the Flames weren't playing me, he sensed a chance to bring me in to bang with young Jagr.

Not once did I hear that from anyone in the clubhouse. It was only years later that I heard from people who took credit for it and told me that they convinced Craig to get me as Jagr's tutor.

For myself, it was important that I scored a goal in the first game against Calgary and felt a great sense of satisfaction. And the fact that Mario came back soon after and we started to make an unbelievable run.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey And it went well with Jagr. They sat us next to each other in the booth, he took me to the Nemec family where he lived, and we became friends. I wasn't playing teacher, because Jarda really just needed someone he felt comfortable around and could talk to. Someone who could help him get comfortable in a new world and who could explain to him in a clear way what the NHL is all about and how to approach certain situations. It was small things, but in sum, pretty important. The same little things that Hakan explained to me in my early days in Calgary and that I just passed on, first to Alby Reichl and now to Jagr.

There was only one problem with him. Sometimes he would step on the gas in the car and he didn't want to pay the fines. He even ended up in court a few times and Craig had to vouch for him with the police. That's when he talked a lot of sense into Jard.

I had no idea at the time what a phenomenal hockey player he would grow up to be. Yes, I'd seen him as a youngster in the national team, but that didn't mean that much. But it's true that he showed incredible things in his first seasons in the NHL. After all, everyone remembers his famous goal in the '92 finals against Chicago, when he flipped Franta Kucherov between his legs and sent a backhand pass to Belfour.

I also had my moment of glory next to him when I managed to score two goals in the first playoff game in the seventh game of the opening round against the Devils. Just recently I saw a table on Canadian TV showing who had two goals for Pittsburgh in the seventh game, because nobody had more. There was Crosby, Rust, Talbot. And the Hero.

Honestly: The goal I'll always remember as the one that made my dream come true will be the lid call on Tretiak after Ruz's pass down the blue line. He got us silver at the 1983 World Championships. But this game against New Jersey is one to remember. I had a great feeling inside at the time, thinking, I guess I'm not that old yet. On that first and finally winning goal, the Russians were on the ice, i.e. defenseman Fetisov Kasatonov. It always made me happy when I helped beat them.

Ironically, it was also my only two goals in the playoffs ever.

Two goals, three Stanley Cups. **** lucky guy, you know.

I was lucky as hell to get on two fantastic teams in the NHL. In Calgary, incredible teamwork led us to the Cup, we were able to dominate through hard work even without pure superstars, we stuck together as one big group of friends. It was in Pittsburgh that an incredibly loaded roster full of amazing players finally clicked. Paul Coffey, Larry Murphy, Ron Francis, Kevin Stevens, Marc Recchi, Jagr, they were all great guys. And finally, we got that Rick Tocchet guy.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockeyAnd Mario was the king of all.

The way he came back from the sideline speaks volumes about how unique a player he was.

After ten months without hockey, he got on his bike for three days, then took to the ice with us twice, and after less than a week of light training, he went to play in Quebec, where he recorded three goals. After three games he was 2+4 and continued in that vein.

He was a classic leader by example. One who leads by example. He wasn't one for making speeches, if he said anything it was more likely to be in the playoffs, but his excellence at the plate was unmatched. He gave you confidence just by seeing him in the locker room getting dressed in the gear next to you. Other than that, he was a friendly, nice guy. He talked to everyone as equals, no condescension. When we finally made it to the Stanley Cup with his great help, he invited the whole team over to his house.

We ended up with the Cup in the pool there, which is one of my fondest memories of the celebration.

Then, my second year in Pittsburgh, I got to know another one-of-a-kind person in the league. Scotty Bowman took over and I found out why he is the most successful coach in history.

In games, it should be added.

There, he showed a really hard-to-describe feel for knowing what line was doing well and on whom. He deployed players like no one else and was able to keep the team on a roll. He was incredibly knowledgeable about hockey, knew everyone's strengths and weaknesses and was able to take advantage of them.

It was just his training sessions that were crazy.

As detailed as he was, he would cling to complete useless things, like we could only turn to one side during a particular drill or something. We all resented it, and morale went down. For example, when he would chase us around in circles and we had to speed up on a whistle, or slow down on the next one, I would whistle to him that there was a maglajs in it. Then he'd yell angrily who was doing it.

So Mario went to Craig and told him that it couldn't be done that way, that the assistants should run the training sessions and that Scotty should only ever show up for the game.

They were both able to accept that, and that helped us to our second Stanley Cup.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

The celebrations, which were unforgettable in Calgary when tens of thousands of people lined the streets during the parade, were worth it here both times. The first year we drove through the city to the 60,000-seat Three Rivers Stadium for American football and baseball. We were each driven around in a convertible, making a circle before being dropped off at the podium. The year after that was celebrated in the local central park, which was again packed with people. I remember images from here that will never fade from my mind. Partly because I recorded them on camera.

Yeah, even back then. It wasn't quite a GoPro, and the picture wasn't exactly HD quality, but a small one-handed camera was something you could get. Admittedly, just about anyone doesn't have such a treasure at home, my friends and I would occasionally play the footage.

But then once we went on to the boat party, I didn't record anything. I couldn't.

Shortly after the second Pittsburgh party, I made an appointment at Craig's office. He welcomed me, saying I'd get so-and-so raises, but that he could only give me a two-year contract.

I said, "Craig, Craig, wait. I'm not here to sign a contract. I'm here to say goodbye to you. I'm done with hockey."

It was quiet for a while.

"Are you serious?"

"Yeah. Dead serious."

He was expecting me to bid on money and contract length, and I surprised him with this announcement. We shook hands and it was done. To this day, Craig gives credit to the fact that there have been so many times in his career that he's offered someone an extension and better money and they turned him down. But I felt enough was enough. I was fed up with hockey after seventeen years of playing professionally. My shoulder was hurting, I was finishing the season with a knee brace due to strained ligaments, and I couldn't imagine starting summer training again after another Stanley Cup celebration. I could have continued in Switzerland or Germany, I had offers from there as well, but the idea that after what I had experienced I would be back on buses somewhere again, discouraged me as well.

World champion, three times Stanley Cup... I figured that this is enough, I can hang it up with peace of mind and rather than risk killing my body, I'd rather keep my strength up and play sports just for fun. My family and I went straight to Hawaii and that was the end of my hockey career.

Jiří Hrdina, ice hockey

Like this, not definitively. There was one more little twitch.

I was persuaded by old Spartans, Standa Hajdušek, Karel Holý, Láďa Vlček and others, that it was a great idea to play with them in the second league for Velké Popovice.

And so I did. I'll go for it, so I can sweat and enjoy a beer for lunch, right...

But we had a team full of amateurs, guys who came to play after work. They'd just been promoted from the county competition, and they weren't really up to the higher competition. My fourth game we came to Havlíčkův Brod.

It was sold out, and they borrowed a line of young guys from Pardubice. We got 1:14.

I scored our only goal. Basically, almost like Lanny McDonald in his last game, you could say... But seriously, I immediately told the guys that I'm sorry, but after everything I've been through, I'm really not up to this anymore. I've never played a competition since. Occasionally, I'll just go out with the old guard, but over the years I've gotten to enjoy just being able to knock somebody around, no golfers or points. And I keep myself busy with tennis and golf, that's enough for me.

Mostly, I'm always at hockey, so I don't miss anything in life.